Neonatal Sepsis is a blood infection that infants may develop before reaching 90 days of age. Babies can also develop early-onset and late-onset sepsis.

Causes?

A bacteria named Eschericia coli (E coli) and Listeria can cause infants to develop sepsis. A specific streptococcus strain (Group B streptococcus or GBS) can also make an infant ill. If the baby’s mother contracts herpes simplex virus (HSV), this can also lead to neonatal sepsis.

An early-onset case usually develops 24 to 48 hours after the baby’s birth, usually by being exposed during birth.

Contributors to early-onset sepsis:

- Preterm delivery

- GBS colonization during mother’s pregnancy

- Placental tissues and amniotic fluid become infected (chorioamniontitis)

- Early rupture of membranes (more than 18 hours)

Late-onset sepsis risks:

- Extended hospitalization for infant

- Keeping a catheter in baby’s blood vessel for an extended time

Symptoms?

- Breathing problems

- Changes in body temperature

- Decreased bowel movements or diarrhea

- Reduced movements

- Low blood sugar

- Reduced suckling

- Heart rate is fast or slow

- Seizures

- Vomiting

- Swollen abdomen

- Jaundice (yellow skin and whites of eyes)

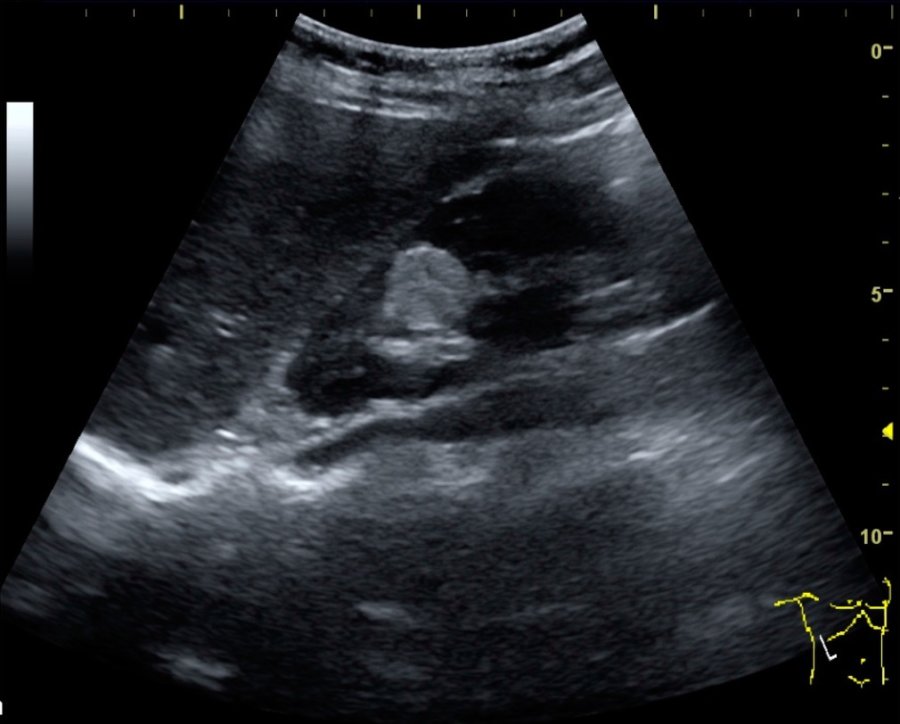

Diagnostic Tests?

Pediatricians perform the following diagnostic tests:

- C-reactive protein

- Blood culture

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Lumbar puncture

- Urine, skin or stool cultures to search for herpes virus

- Chest X-ray (if baby has difficulty breathing)

- Urine cultures

Treatments?

Even if the newborn is symptom-free, they will receive intravenous antibiotics. Babies younger than 4 weeks with fever or other symptoms receive IV antibiotics immediately.

The baby stays on antibiotics for three weeks if bacteria is in the spinal fluid or blood. This is shorter if no bacteria is present.

Acyclovir (antiviral medication) is given for HSV-caused infections.

If the baby has already gone home, it will be re-admitted to the hospital for treatment.

Outlook?

The infant may recover completely and show no evidence of any other problems. Neonatal sepsis can lead to infant death. The sooner treatment starts, the better the prognosis.

Potential Complications?

- Disability after illness

- Death

Prevention?

Pregnant mothers should receive preventive antibiotics if they have these illnesses:

- Group B strep colonization

- Chorioamnionitis

- Has already had a baby with bacterial sepsis

- This condition is preventable. Babies should be delivered 12 to 24 hours after water breaks.

Other Names?

Other names include:

- Neonatal septicemia

- Sepsis – infant

- Sepsis neonatorium